By Mike Wistow for Folking.com, a lovely review of my book So Sound You Sleep, available from Amazon here. (As paperback or as eBook.)

By Mike Wistow for Folking.com, a lovely review of my book So Sound You Sleep, available from Amazon here. (As paperback or as eBook.)

I’ve linked to this song before elsewhere, but as I’ve added quite a lot of background info this time, I thought it was worth a post of its own. And it suddenly struck me that if it was worth posting on my Cornish blog, it probably merited a post on my Shropshire blogs.

Wrekin (The Marches Line) (words & music by David Harley)

The Abbey watches my train crawling Southwards

Thoughts of Cadfael kneeling in his cell

All along the Marches line, myth and history

Prose and rhyme

But these are tales I won’t be here to tell

The hill is crouching like a cat at play

Its beacon flashing red across the plain

Once we were all friends around the Wrekin

But some will never pass this way again

Lawley and Caradoc fill my window

Facing down the Long Mynd, lost in rain

But I’m weighed down with the creaks and groans

Of all the years I’ve known

And I don’t think I’ll walk these hills again

Stokesay dreams its humble glories

Stories that will never come again

Across the Shropshire hills

The rain is blowing still

But the Marcher Lords won’t ride this way again

The royal ghosts of Catherine and Arthur

May walk the paths of Whitcliffe now and then

Housman’s ashes grace

The Cathedral of the Marches

He will not walk Ludlow’s streets again

The hill is crouching like a cat at play

Its beacon flashing red across the plain

Once we were all friends around the Wrekin

But some will never pass this way again

And I may never pass this way again

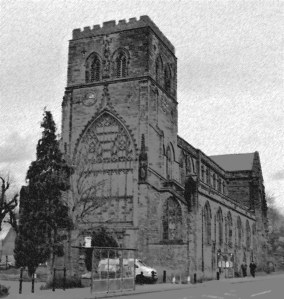

‘The Abbey’ is actually Shrewsbury’s Abbey Church: not much else of the Abbey survived the Dissolution and Telford’s roadbuilding in 1836. Cadfael is the fictional monk/detective whose home was the Abbey around 1135-45, according to the novels by ‘Ellis Peters’ (Edith Pargeter).

The Welsh Marches Line runs from Newport (the one in Gwent) to Shrewsbury. Or, arguably, up as far as Crewe, since it follows the March of Wales from which it takes its name, the buffer zone between the Welsh principalities and the English monarchy which extended well into present-day Cheshire.

‘The hill’ is the Wrekin, which, though at a little over 400 metres high is smaller than many of the other Shropshire Hills, is isolated enough from the others to dominate the Shropshire Plain. The beacon is at the top of the Wrekin Transmitting Station mast, though a beacon was first erected there during WWII. The Shropshire toast ‘All friends around the Wrekin’ seems to have been recorded first in the dedication of George Farquar’s 1706 play ‘The Recruiting Officer’, set in Shrewsbury.

‘Lawley’ refers to the hill rather than the township in Telford. The Lawley and Caer Caradoc do indeed dominate the landscape on the East side of the Stretton Gap coming towards Church Stretton from the North via the Marches Line or the A49, while the Long Mynd (‘Long Mountain’) pretty much owns the Western side of the Gap.

Stokesay Castle, near Craven Arms, is technically a fortified manor house rather than a true castle. It was built in the late 13th century by the wool merchant Laurence of Ludlow, and has been extensively restored in recent years by English Heritage, who suggest that the lightness of its fortification might actually have been intentional, to avoid presenting any threat to the established Marcher Lords.

Prince Arthur, elder brother of Henry VIII, was sent with his bride Catherine of Aragon to Ludlow administer the Council of Wales and the Marches, and died there after only a few months. Catherine went on to marry and be divorced by Henry VIII, and died about 30 years later at Kimbolton Castle. Catherine is reputed to haunt Kimbolton, so it’s unlikely that she also haunts Whitcliffe, the other side of the Teme from Ludlow Castle. (As far as I know, no-one at all is claimed to haunt Whitcliffe. Consider it poetic licence…)

For some time it has puzzled me that in ‘A Ballad for Catherine of Aragon’, Charles Causley refers to her as “…a Queen of 24…” until I realized he was probably referring not to her age, but to the length of time that she was acknowledged to be Queen of England.

The ashes of A.E. Housman are indeed buried in the grounds of St. Laurence’s church, Ludlow, which is not in fact a cathedral, but is often referred to as ‘the Cathedral of the Marches’. It is indeed a church with many fine features (I have about a zillion photographs of its misericords) and its tower is visible from a considerable distance (and plays a major part in Housman’s poem ‘The Recruit’).

The song was actually mostly written on a train between Shrewsbury and Newport at a time when I was frequently commuting between Shropshire and Cornwall to visit my frail 94-year-old mother, who died a few months after, so it has particular resonance for me. It originally included a couple of extra verses about Hereford and the Vale of Usk, but after the ‘Wrekin’ chorus forced its way into the song, I decided to restrict it to the Shropshire-related verses. Maybe they’ll turn up sometime as another song.

David Harley

First (unaccompanied) demo.

Backup:

This is the second demo version: still rough, but now with some basic guitar. Relates to Shropshire rather than Cornwall: you can take the boy out of Shropshire, but you can’t take Shropshire….

Backup:

I came across this set of words in a discussion on the Memories of Shropshire Facebook group, and somehow found myself putting a tune to it as I read. This version of the tune is one of my ‘make it up as you go along’ recordings: it may well change significantly over time, and is not in any case consistent between all the verses.

By W.B.H. and apparently dated 29th May 1786, though that may have referred to the wedding that took place on that date rather than the date of printing. It seems that the modern Arbor Day celebration is held on the last Sunday in May rather than strictly on the 29th. The Aston Clun celebration is closely linked with Oak Apple Day as well as with the wedding of 1786. I don’t know exactly when this was published, but the somewhat random initcapping and the use of a ‘thin space’ before colons and question marks is characteristic of an earlier school of typography, perhaps as far back as the late 18th century.

In Aston Clun I stand, a tree,

A Poplar dressed, like a ship at sea.

Lonely link with an age long past :

Of Arbor Trees, I am the last.

Since seventeen-eighty-six, My Day

Is writ, the twenty 9th of May.

When new flags fly and we rejoice,

New life has stilled harsh Winter’s voice.

To greet a Squire’s lovely bride

Did tenants dress my boughs with pride ?

But Old Wives say, my flags are worn

To mark the day an heir was born.

Wise men, mellow o’er evening ale,

Old feuds and wicked deeds retail.

Thanksgiving dressed my arms, they say

For Peace, when blood feuds died away.

Did here ! my father mark the rite

Of Shepherd’s, gone with world’s first light ?

Was England merrie neath his shade

Till crop-Haired Cromwell joy forbade ?

In sixteen-sixty with the Spring

Came Merry Charles the exiled king.

Did he proclaim May twenty-nine

“Arbor Day” for revelry and wine ?

And Shepherds, plagued with pox and chills

Turn to the old ways of the hills,

To “Mystic Poplar”, to renew

Fertility in field and ewe ?

Stand I, for Ancient ways, for Birth,

For Love, for Peace, for Joy and Mirth?

Riddle my riddle as you will

I stand for good and not for ill.

And if my dress your fancy please

Help my flags to ride the breeze

That you with me, will in the Sun,

Welcome all, to the Vale of Clun.

A Research Article from April, 2003, by John Box gives some very useful information. It’s available from a number of places including here.

Here’s the Abstract:

The custom of dressing the black poplar growing in Aston-on-Clun in south Shropshire – known as the Arbor Tree – with flags on flagpoles every 29 May is unique in Britain. New flags are attached to wooden flagpoles on the tree that remain throughout the year. Written records of the Arbor Tree only extend back to 1898, but the tradition of dressing the tree is reputed to date back to a local wedding in 1786. The article attempts to establish the history and context of the tradition and shows how the custom has developed and acquired new meanings, particularly since 1955 when a pageant was devised. The pageant and the celebrations associated with the tree dressing are evolving in response to those living in the local community as well as to the external recognition now accorded to this unique tradition.

David Harley

Since I now live in Cornwall, I tend not to have much to say about Shropshire these days. However, I have been reminded twice in the last couple of days of The Raven, the rather pretty Shrewsbury hotel and former coaching inn which was pulled down nearly 60 years ago and replaced with a rather brutalist Woolworths (now another store, though I can’t remember which). This morning, I came across this excerpt from The Recruiting Sergeant by George Farquhar (d. 1707), himself a recruiting officer who often stayed there.

‘…if any servants have too little wages, or any husband too much wife, let them repair to the noble Sergeant Kite, at the sign of the Raven in this good town of Shrewsbury…I don’t beat my drum here to ensnare or inveigle any man, for you must know, gentlemen, that I am a man of honour!’

While a couple of days ago, while watching a dramatization of Howards End (a book I still remember quite well from Eng. Lit. in the 1960s!) with my wife, I mentioned The Raven to her in the context of a visit to Oniton (a fictionalized version of Clun).

‘At Shrewsbury came fresh air. Margaret was all for sight-seeing, and while the others were finishing their tea at the Raven, she annexed a motor and hurried over the astonishing city.’

I shall be interested to see if that little scene makes it to the TV series.

While doing a little fact-checking for this article, I came across this page on Shropshire Literary Connections, which included a couple of connections I hadn’t been aware of. I was particularly entertained by the thought of Wycherley escaping from Wem to London and then escaping back to Shropshire from time to time in order to evade his creditors. One connection it doesn’t mention is Oscar Wilde: in The Importance of Being Earnest Algernon claims that ‘I have Bunburyed all over Shropshire on two separate occasions.’ And Wilde himself apparently lectured at the former Theatre Royal (now flats and retail properties, I think) in 1883.

* Slightly misquoting Poe’s The Raven:

Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore—

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

David Harley

I think I’ve probably made my own feelings clear on the topic of people who believe that there is only one way to pronounce Shrewsbury and anyone who thinks differently is stupid or worse, but if you’re interested in the recent debate at the University Centre in Shrewsbury, there was a video here. But it seems to have moved or been removed.

I never got around to watching it, as it represented some 53 minutes of my life that I might want back afterwards. As one of Phil Rickman’s characters says: ‘I don’t get panic attacks…I’m a professional. I get faintly irritated attacks.’ (From Night After Night.) Though hopefully it represents a more civilized discussion than some of those on Facebook.

David Harley

I should probably just drop any Facebook page that keeps reviving the argument about whether the first syllable of Shrewsbury should be pronounced Shrow or Shrew (or even Shoe). Not that the topic doesn’t have historical interest: it’s just that some of the people who engage with the discussion have an unpleasant tendency to dismiss anyone pointing out that there are viable alternative views as stupid or snobbish, and reading their outbursts is bad for my blood pressure.

As I’ve already pointed out in an update to my previous blog on the topic, the BBC did recently (July 2015) report an attempt to ‘settle‘ the debate. Of course, it did no such thing, though a majority of respondents (58%) did vote for ‘Shroosbury’ (it’s not clear whether or how the ballot distinguished between Shroosbury and Shoosbury – 7% of respondents did vote ‘other’). That’s hardly surprising: those are the ways in which most people pronounce it nowadays. And I’m certainly not going to tell them they shouldn’t. However, the point that seems to be missed time and time again is that this isn’t an argument with only one correct answer: it’s a matter of preference, and while I’m pleased that the debate was apparently not only quite civil but raised money for a worthwhile charity, I don’t think it’s ‘settled’ anything, any more than two blokes arguing in the pub can ‘settle’ disputes about foxhunting or immigration with any authority.

It’s perfectly reasonable to pronounce it with an ‘oo’ because that’s how most other people pronounce it. To pronounce it to rhyme with ‘sew’ because there is historical/traditional/etymological precedent is also perfectly reasonable. At least, I always thought so, though to be honest I’m probably also influenced nowadays by my dislike of the sheer bad manners of some of those who disagree.

All that said, I was delighted to read (on Facebook, where else?) that the correct pronunciation is with an ‘oo’ because ‘shrews are on the coat of arms not shrows,’

Well, there has been some discussion about Shrewsbury’s coat of arms (and indeed Shropshire’s, which is similar but by no means identical). Both feature representations of three animal heads, but the argument is usually about whether the heads represented should be those of lions or of leopards (both seem to have been used over from time to time. In fact, an article from 2008 in the Shropshire Star tells us that:

Robert Noel, Lancaster Herald at The College of Arms, who investigated the case using ancient manuscripts, said: “Many, or even most, early heralds did not trouble to distinguish very clearly between lions and leopards.

However, a document from the reign of William III specifically refers to ‘leopard’s faces’, also according to Mr Noel.

This isn’t the only controversy, mind you. The pub formerly called The Shrewsbury Arms (at any rate since the early 19th century), now better known as The Loggerheads, takes both its names from Shrewsbury’s heraldic arms, featured on the pub sign. The more recent name derives from the use of the word ‘loggerheads’ to describe leopard faces in heraldry. One source speculates that this comes from ‘the practice of carving some such motif on the head of the log used as a battering ram’. However, in 2004 there was a great deal of fuss when the brewery replaced the pub sign with one showing a Loggerhead turtle. Logical (so to speak), but nothing to do with the history of the pub.

So here’s a link to the town’s coat of arms, or at least the representation to be found on Wikipedia. And here’s the Shropshire country flag, also according to Wikipedia. And apparently Shropshire, now a unitary authority as well as a county, still uses this representation of its official blazon, as granted in 1896 to the county council.

Well, I’m no zoologist, but all those faces look more like a big cat than a common shrew to me. But what do I know? After all, I can’t even pronounce Shrewsbury. 🙂

David Harley

A recent mention in a Facebook group of Iona Opie reminded me that in one of her books with Peter Opie they mention children Maypole dancing in Monkmoor. I don’t have immediate access to the book, and indeed I’m not sure which one it was, though I suspect that it was either The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren or Children’s Games in Street and Playground . It was, after all, in the 70s that I read it. I believe they were writing about the late 50s and possibly very early 60s.

The recollection has stuck with me – though I can’t say how accurately – because I lived in Monkmoor in the 1950s and remember seeing older children on at least one Mayday dancing in the street. My admittedly faded memory is in accordance with Roy Palmer’s description in ‘The Folklore of Shropshire’. As he includes The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren or Children’s Games in Street and Playground in his list of references, I suspect that’s the book I read back in the 70s.

He describes how in Monkmoor (and indeed in Ditherington) children set up maypoles ‘consisting of a pram wheel decorated with red, white and blue crepe paper and streamers, and set on the top of broomstick so that it could revolve. The May queen sat on a stool and held the pole while other girls danced round and sang…’

What did they sing, you may wonder?

The first verses of the song as printed by Palmer closely resembles other songs known at least in the West and East Midlands, and very possibly further afield.

Round and round the Maypole merrily we go,

Tripping, tripping lightly, swinging to and fro.

[or ‘Singing hip-a-cherry, dancing as we go]

All the happy pastimes [or ‘children’] on the village green,

Hurrah ! Hurrah! Hurrah! May queen

[Or ‘Sitting in the sunshine, hurrah for the queen!’ or ‘Sporting in the sunshine with our flowery queen]

The queen would sing something like:

I’m the queen don’t you see

I’ve just come down to the village green

[or ‘I have come from a far country’]

and if you wait a little while

I will dance a may pole style.

A version from the East Midlands then goes into a pair of couplets reminiscent of the ‘Oh you New York girls, can’t you dance the polka’ chorus from a well-known sea song. Palmer, however, shows a lyric vaguely related to ‘three cheers for the red, white and blue’ words often associated with Souza’s march ‘The Stars and Stripes for ever’, immediately followed by a snatch of ‘Rule Britannia’. Perhaps these patriotic sentiments were related to the still fresh memories of World War II?

While the maypole seems to have had something of a revival in English schools in recent years, I don’t remember any of these activities being encouraged at the nearby Crowmoor school, where I got nearly all my own pre-secondary schooling. My own turn around the maypole came in the very early 1960s, when I spent my last term as a junior at the recently-established Harlescott Grange Junior School. Astonishingly, I can still remember the tune to ‘Come Lasses and Lads’ to which we sang a set of words very similar to the lyric here. Here’s an extract from a slightly different version, as quoted in Spring in a Shropshire Abbey, by Lady Catherine Henrietta Wallop Milnes Gaskell

“Come lasses and lads, take leave of your dads,

And away to the May-pole hie;

For every he has got him a she,

And a minstrel standing by.

For Willy has gotten his Jill,

And Johnny has got his Joan

To jig, to jig it, jig it up and down.”

There’s a demo version of the first verse here:

And that was pretty much it for me and Mayday. At any rate, until learned the splendid tune ‘Staines Morris’ (or ‘Stanes Morris’) a few years later. Staines is quite a long way from Shropshire, though, so maybe I’ll come back to that in another article.

Roy Palmer’s ‘The Folklore of Shropshire’ is published by Logaston Press,

David Harley

We were hit by a snow flurry hard enough to make it virtually impossible to get outstanding photos of the stone circle itself – at any rate with my little compact – but the light was pretty dramatic and a little Photoshopping has improved some of the close-in shots.

The circle is over 3,000 years old and the stones are dolerite from Stapeley hill. Continue reading

This is the White (or West Grit) Engine Shaft near White Grit(t), a village on the border between Shropshire and Powys. The village gets its name from the lead mine operated there and at the East Grit (a.k.a. Old Grit) shaft by the Whitegritt Mining Company. The West Grit shaft is located near Bishops Castle, in a field at the junction of the A488 and the road to Priest Weston (which leads to the village and to the stone circle at Mitchell’s Fold.

The A488 runs between the Engine Shaft and the hill with the copse at the top.

The shaft itself is completely blocked, and the tips have long since been removed for road building.

David Harley

Small Blue-Green World

If you’ve looked through this site, you may have noticed that I’m quite fond of the poetical works of A.E. Housman, whose remains can be found in St. Laurence’s churchyard in Ludlow, not five minutes walk from where I’m sitting right now.

Which explains why I have a short-ish article in the January-February issue of Ludlow Ledger entitled While Ludlow Tower Shall Stand, about my personal voyage into the Housman’s world. The title of the article comes from A Shropshire Lad III (The Recruit) and while it’s quite suitable for the content of the article, I hadn’t realized at the time I wrote it that Clive Richardson had used a very similar line from the same poem for his book Till Ludlow Tower Shall Fall, or else I’d have used a different title. Sorry, Clive! Still, I don’t suppose my little article is going to affect the sales of your book adversely. 🙂

[As far as I can tell, Ludlow Ledger is no longer active, but the issue linked above is still functional at the time of writing – March 2023.]

David Harley